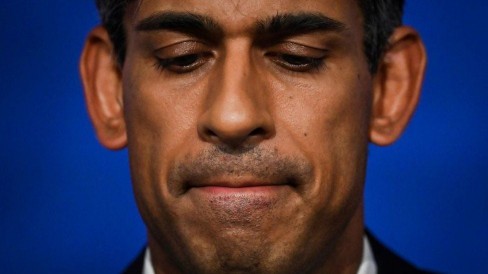

Net zero: Will Rishi Sunak's changes to climate policies save money?

Rishi Sunak's decision to extend some of the UK's net zero deadlines has proved - perhaps predictably - rather divisive.

The prime minister said he was putting "the long-term interests of our country before the short-term political needs of the moment".

Supporters say the planned green policies, including a 2030 ban on new petrol cars, would have hit people too hard financially, especially in such inflationary times.

Critics, however, say taking longer to reach net zero will damage the UK's economic prospects, undermine business confidence and leave us behind in the global race for investment, they say.

Even some of Mr Sunak's own MPs have warned that backtracking could cost jobs and push up energy bills in the future.

So will the changes mean more money in people's pockets, as Mr Sunak's supporters claim? And what does a slower move to net zero mean for the UK economy?

- What does net zero mean?

- Cars, boilers and other key takeaways from Sunak's speech

- Is the UK on track to meet its climate targets?

Mr Sunak says that "some of the things that were being proposed" - such as bans on new petrol and diesel cars and new gas boilers - "would have cost typical families upwards of 拢5,000, 拢10,000, 拢15,000".

However the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU), an independent think tank, has pointed out that no one was being forced to take up these measures immediately.

The planned ban on the sale of gas boilers was not due to start until 2035, it says. The policy also only applied when a boiler broke or a person chose to switch.

The think tank added that the PM cancelling new energy efficiency regulations for the private rental sector could cost British households almost 拢8bn in higher bills over the next decade - and more if gas prices spike again.

ECIU director Peter Chalkley said that the changes to net zero policy would "add to the cost of living for those struggling, not make things easier".

Meanwhile, Matthew Agarwala, a University of Cambridge environmental economist, described the overall changes as "reckless".

"Renters face longer in lower quality homes, the public faces toxic air pollution for longer," he said. "And rather than taking control of transport costs with domestic renewable electricity, drivers are left exposed to the whims of international oil prices," he says.

Will delaying petrol car ban help?

Pushing the ban on petrol and diesel engines from 2030 to 2035 is expected to have a "limited" effect on people's pockets, according to sources in the motor industry.

The majority of people buy second-hand cars and the ban only relates to the sale of new vehicles.

Some in the car industry worry that the government is sending mixed messages - on one hand, telling manufacturers to make more electric cars with strict sales targets and fines for failure due in 2024, while on the other, appearing to tell consumers that they can put the brakes on switching.

Analysts suggest that to meet sales quotas, car-makers may have to make electric vehicles cheaper. A new electric vehicle on average costs 39% more than its petrol or diesel equivalent.

And there are concerns about Sunak's announcements outside the car industry, too.

On gas boilers, industry group Energy UK said some of its members were pleased with the plan to boost grants for heat pumps and announcements on fast-tracking energy grid projects.

However, its chief executive Emma Pinchbeck said members were mainly concerned about "uncertainty" and "change in tone" from government when it comes to them making investment decisions.

"Money moves," she said. "And there are now other places in the world going faster than we are."

'Economic pain' of net zero?

How will the switch to net zero impact the economy? Some of the costs of moving to a low-carbon economy are daunting, and jobs will undoubtedly go in old carbon-intense sectors.

Stuart Adam, senior economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, says some net zero policies could be a win-win for the economy and the environment - but warns there "there will be some [economic] pain" in the transition.

As an example - a deal to keep the biggest steelworks in Britain open at Port Talbot will save 5,000 jobs, according to the government. The flip side is that up to 3,000 will still be lost.

Image source, PA Media

The government has already agreed to give 拢500m to Tata for the Port Talbot deal. The firm, which owns Jaguar Land Rover, will also get hundreds of millions in subsidies to build a new 拢4bn electric car battery factory in Somerset.

Nissan has also secured 拢100m in public money towards a 拢1bn investment in expanding a Chinese-owned battery plant in Sunderland, and BMW has announced plans to invest hundreds of millions to transition its Mini factory in Oxford to electric car production.

Chris Stark, the chief executive the UK's Climate Change Committee (CCC), said that such huge subsidies are "very tricky" in the short term - using the public purse to drive change can hit ordinary pockets.

However the CCC, which oversees the government's progress on reducing greenhouse gases, estimates that short-term costs could be completely offset by long-term benefits.

Mr Stark said that overall the transition may well deliver jobs and growth that wouldn't be there without it - an "invest-to-save" scenario.

The independent consultancy Oxford Economics has concluded that forging ahead with transition could act as a catalyst for private-sector investment and boost the UK economy by 2050.

Mr Agarwala, the environmental economist, said there was a risk that some people may be seeing things through "green-tinted glasses" that blur the impact of immediate costs.

However, he argues that those costs won't necessarily be as high as some fear.

Prices for green technology will continue to fall, he predicts, just as prices for solar and wind power have already plummeted.

"Either we face the upfront investment costs, which, like all other investments, yield benefits in the future," he said.

"Or we face the climate catastrophe costs, which yield no benefit, only disaster."